“Well, if one knew what the future held, say, defeat or even victory,

would he try less hard, or instead more so, depending on what he knew?

And if he changed his conduct because of knowing,

and thereby changed the outcome, would he not thwart Destiny,

and thus perhaps upset the balance of all?”

Alain fell silent and looked ’round the table at pondering faces.

Then he reached out and laid his hand atop Camille’s and

grinned, saying, “Besides, instead of knowing the future;

I’d much rather be surprised.”

Dennis L. McKiernan, Once Upon a Winter’s Night

Brief Considerations on Determinism

in Reality and Fiction

©Frank Weinreich

Abstract

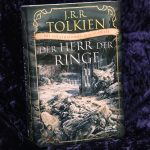

Determinism plays a crucial role in considerations on ethics and free will. This is true for the real world as well as for invented worlds like Middle-earth. This paper discusses the issue of determinism and non-determinism in reality and fiction on a basic level and in conclusion shows how free will might very well exist as a fact in the invented world of Middle-earth.

The article first apperead in: Frank Weinreich/ Thomas Honegger (eds.): Tolkien and Modernity 1, Zürich, Bern 2006b. 135 – 144.

Why might determinism be a problem in reasoning about J.R.R. Tolkien’s fictional work? It is because the question of determinism plays a crucial role in every ethical discussion of free will, regardless whether it turns up as a topic in reality or in fiction.1 If one assumes (or refutes) the existence of free will and therefore responsibility for one’s actions as well as one’s omissions, this assumption depends on one’s understanding of determinism and on the exact nature of determinism.

If, on the one hand, one has to conclude that binding determinism rules everything that is happening or undertaken, than no one can be singled out and given responsibility for the results of certain undertakings or omissions.

If, on the other hand, one argues that determinism is not given or that its reach does not cover completely the outcome of the reasonings of sentient beings, then persons can be blamed or praised for their actions.

This is true for both reality – or the Primary World, as Tolkien would have said –, and for fiction – the Secondary, or Subcreated Worlds. Thus, considerations on free will and, consequently, also on determinism play an important role in the interpretation of Tolkien’s works – the stories and lays of Middle-earth being what they are: reports on the struggle between good and evil carried out by or on the backs of free or enslaved Valar, Maiar, Elves, Orcs, Hobbits, Trolls, Dwarves, Dragons and Men.

Determinism in the Primary World2

Physical and physiological processes, including the observable3 processes inside the brain which, as far as science can say, lead to every deliberate action of sentient beings, are part of a chain of causes and effects which does not allow for any freedom in the sense of breaking out of said chain. It was this chain of cause and effect that back in 1812 made the French physicist Pierre-Simon Laplace claim that he could describe the exact state of the universe at any point in the future, if only he had sufficient means to calculate the data. While this was a slight exaggeration, Laplace was right in principle. Everything is part of cause and effect relations and therefore computable in principle, at least as long as the world is seen as monistic.4 And every speculation on metaphysical constructs or beliefs are just this – speculative.

The consequence of this seems to be that the world is deterministic. This is even true in the light of quantum mechanics, as Nikolaus Knoepfler has pointed out. Even if on a subatomic level nondeterminism might be a fact, which is not proven (1997:103), there exists no necessary conclusion that nondeterminism on the micro level leads to nondeterminism on the observable macro level – and even if it did, random subatomic processes would still determine the processes on the macro level, which does not lead to freedom and free will of sentient beings (103). Again, even considering the quantum level, determinism rules the universe as long as one does not take refuge in dualistic world views.

But does this observation really constitute such a problem in ethical reasonings? It does! But then, does it really lead to the dreaded anarchy of ubiquitous non-responsibility? At first sight, determinism is very problematic indeed. Yet if one takes a closer look first at the difference between determinism and predictability and, secondly, at the life people actually lead, the loopholes for evil doers, claiming they could not act otherwise than they had, for “I couldn’t help myself, Sir”, can be plugged.

The important difference between predictability and determinism gets confused sometimes. Chaos Theory might provide a good picture of this. One of the main realizations of Chaos Theory5 is the unpredict¬ability of everything. Seemingly minimal events can have immense effects. Often the famous butterfly wing in the South American rain forest is mentioned as an example: the beating of one butterfly wing is said to cause a minimal irritation of currents in the warm jungle air that, by means of various amplifying confluences, cause a hurricane in Florida. Of course, one would hardly think of that when enjoying the beautiful play of sunlight on the blue wings of Morpho peleides while vacating in Brazil. And that is exactly the point of it. If one would catch the butterfly the moment before it makes its fateful fluttering, one could save lives and properties. Is the person to blame who does not do so? Only in the case if she knew what would occur … and that she can never know, because, as Chaos Theory states correctly, that is simply not predictable. And yet it was the wing of the butterfly that determined the outbreak of the storm. For ethical reasonings this means that, though there is a deterministic flow of causes and effects, people are still obliged to do what is probably right6 at the moment they consider a certain action.

If people started to catch every butterfly they could lay hands on, it would most likely not result in peaceful weather all around the world. But to stick a knife between someone’s shoulder blades would most probably affect that person negatively. For practical purposes, common sense and the jurisdiction correctly assume that there is so much freedom in people’s behaviour that choices between doing something and omitting that something are given.7 The point in the discussion of unpredictability and determinism is that though everything in the material world is embedded in a chain of cause and effect, the actions of people are free in so far as human beings can predict the consequences of their actions in most ethical relevant cases to such an extent that one can act according to this outlook, and in consequence can be held responsible for one’s deeds.8 This assumption is also called “practical realism“ (“praktischer Realismus”, Knoepfler 1997:112): “Our whole life is witness to the assumption that we think our lives are, within certain limits, at our disposal” (114).9 This realism earns the label ‘practical’ since it integrates the scientific realization of determinism with the daily experience of freedom, thus admitting a practical (and morally as well as legally binding!) form of free will and indeterminism. Although everything is determined (in a monistic weltanschauung, and science can provide no other), man, the human personality, as a result of billions of forming (determining) influences, is an acting entity in its own right that has the capability of making responsible decisions – everything else would be an incapacitation totally incongruent with the daily experience of living in a society.

Determinism in the Secondary world10

The same chain of cause and effect which rules everything in the primary world is also observable in most invented worlds, if only for the sake of allowing the reader to follow the story. Stories which would constantly neglect the patterns of cause and effect would probably be no longer comprehensible. However, it would be possible for an author to break out of the jail of deterministic laws of the Primary World and invent new rules, at least for a part or some aspects of her creation.

But it seems that for Middle-earth, its sub-creator J.R.R. Tolkien does not claim this freedom of the story-teller:11 “The country of the book, Middle-earth, is a land much like our own, as mythical, but no more so. […] It is a world […] subject to natural law” (Beagle 1966:X). Hence Middle-earth is a world in which the principles of determinism rule. And it is a created world, a fact that for the primary world, in which we live, can only be speculated upon. So is everything set on its predetermined way? That might well be so, but it need not necessarily be so. At least two nondeterministic explanations are possible.

The first one questions the extent of determination on a macro level in Middle-earth. The world is created in a deliberate act of will by a supreme being: Iluvatar. Iluvatar uses music for bringing this universe of His into physical being. The accords of this music follow patterns which, in the end, lead to an unavoidable outcome not unlike Judgement Day, which people of Christian faith believe in. It remains unclear whether every detail in the history of Middle-earth is foretold by Iluvatar, and, in consequence, unavoidable, or whether only the general outcome of salvational bliss is determined,12 while the way to this end may just as well tumble along the extremes of unpredictable catastrophes and periods of well being and righteousness through the Ages. It is, for example, possible that the Third Age could have ended with Sauron’s triumph (after all, it was a very close call), followed by thousands of years of utter despair for Middle-earth’s inhabitants. If so, then the concept of sentient beings, as devised by their Maker, might just as well be sufficient to guarantee that at some time in the future of a dark Fourth Age enough pure-hearted people would arise to thwart Morgoth’s servant and allow for a Fifth Age (and possible further ages) until the music is reunited in the last and lasting theme.

The second explanation refers to the fact that Middle-earth is not placed in a monistic universe. The cosmos of Middle-earth is a dualistic one consisting of a material plane (including Valinor) and a spiritual plane, i.e. the nondescript place where Iluvatar resides. At least humans, who do not reach the halls of Mandos after their demise, seem to have a spiritual spark – a soul – and this soul might just as well be free of the restraints of cause and effect, and thus in itself a powerful new movens introduced to the Secondary World.

Alternatively, men also might have been thrown into a macrode¬terministic world in which the victory for Morgoth and Sauron is impossible, just as Iluvatar had prophesied. But even then men still could fail and be judged accordingly – indeed, all of Middle-earth could be a testing place for men. Frodo could have failed and could have claimed the Ring for himself while still walking in The Shire. Fate (Iluvatar) may then have chosen a worthier Hobbit. Under slightly different circumstances, Denethor might have withstood the mental onslaughts of Sauron through the Palantír, but incidents would still have followed nearly the same pattern on the Pelennor, before the Black Gate and at Mount Doom. In a dualistic cosmos these and other scenarios are possible and are not marred by logical faults that might occur within a different setting.

Conclusion

Empirically based scientific reasoning regarding determinism in the Primary World leads to only one realization – we live in a deterministic universe where every incident is embedded in a chain of cause and effect. That incidents are totally unpredictable and, on a quantum level, might just as well be governed by random subatomic processes, does not change this realization one bit. But people live their lives on an ‘as if’-basis, acting ‘as if’ they had a freedom of choice. And, for all practical pur¬poses, the sane mind does indeed have this freedom of choice at her dis¬posal and is able to choose a course of action at her own will. Fictitious worlds, like Middle-earth, follow only the design of their creator and can be deterministic, nondeterministic, or something in-between. Middle-earth, as Tolkien has pointed out, resembles in its makeup the Primary World. Hence it is deterministic on a materialistic level. And even on the spiritual level that is superimposed on the material level of Arda determinism seems to be the dominant concept.

But although Middle-earth seems to be governed by Iluvatar’s will, the efforts of the heroes of the Ring are heroic and testify to a stern will to do the right thing. They testify to a will that would have had the freedom to refuse the tasks of the members of the fellowship at the beginning, at least as far as they know.13 The heroes might lead a deterministic life in the same sense of determinism that we do. But it would also still have been their admirable free choice to endure – the same way someone in the Primary World acts heroic. Yet this Secondary World is not only materialistic; and even though Middle-earth is dualistic, there is still no proof that Iluvatar’s – in principle unalterable – design would not have allowed for freedom and free will in a limited way, as I have tried to point out in the second section of this paper: the determinism may not be absolute, or, alternatively, some of the beings in Arda have been created free. One just cannot say … but I believe that Tolkien meant his creatures to possess free will, else their individual salvations and damnations would lack any meaning.

1 The world in which we are living, the third planet of a certain sun in one arm of the spiral galaxy, called the Milky Way by the inhabitants of the said planet, and the galaxy it is part of, and also the universe in which this arrangement is placed, are hereby referred to as reality. Fiction, for the purposes of these considerations, are stories invented by the inhabitants of said planet. I am aware that the assumption that there exists a certain reality outside the thinking of individuals is disputed by some philosophers and quite a few intellectuals of various professions. This is not the place to discuss the underlying world views that feed these doubts about reality (see Sandkühler 1999a for a brief summary of this problem). It shall only be made explicit that the following reasoning about reality is founded on the “axiomatic as¬sumption” (Mayr 2000:61) that there is a reality; that it is, in its existence as well as in its properties, independent from human reasoning and recognition (Sandkühler 1999b:1042), yet which people consciously as well as unconsciously take for granted. This is proven by the fact that they do take part in discussions, a fact which would be pointless without the assumption of some practical reality, for which Nikolaus Knoepfler coined the term “practical realism” (see below and Knoepfler 1997:112f.).

2 The terminology of one Primary and many Secondary Worlds is based on Tolkien’s writings. In his famous essay ‘On Fairy Stories’ Tolkien calls the world in which we live the “Primary World” and, for invented worlds like Middle-earth or those of other authors, he coins the term “Secondary World[s]”. Both kind of worlds are cre¬ated, the real world by God and the Secondary Worlds by their narrators – a process he defined as sub-creation, created after God’s creation and, for the Catholic Tolkien, of course, in an inferior manner.

3 “Observable“ through certain technical picture producing methods like positron emission tomography and other noninvasive or invasive procedures.

4 Even dualistic world views usually assume cause and effect scenarios, especially in ethical considerations. But since under dualistic or nonmaterialistic beliefs an en¬tity of a different matter, often referred to as the soul, is part of the discussion, it poses no problem to describe this otherworldly matter as free in principle, which on the other hand means that the bearer of this soul is responsible for her actions.

5 See Gleick 1987 for an introduction to Chaos Theory.

6 This is not the place to dwell on what ‘right’ means in this context, since this an abstract line of thought that in (moral) reality depends on the situation and the op¬tions at hand.

7 And where they are not given, as for example in the case of mental illness, or not totally given, as for example in the case of extreme poverty of thieves, the deter¬mining causes for morally and legally wrong behaviour are usually taken into account, at least in modern and democratic jurisdictions.

8 The problem of responsibility increases with the complexity of situations. While it is not hard to determine that violent behaviour against people who cannot defend themselves is not right, it might be hard to judge whether participating in genetic research on gene manipulation is right or wrong in the sense of whether said re¬search may prove beneficial or harmful in the end. But even informed considera¬tions, which, for example, put the benefit of patients above economical interests of the commercial sponsors of that research, can draw sufficient guidelines to morally correct choices for or against the participation in complex issues.

9 “[U]nsere ganze Praxis legt davon Zeugnis ab, daß wir in bestimmten Grenzen über unser Leben zu verfügen meinen” (Knoepfler 1997:114).

10 See footnote 2 for an explanation of the nomenclature of counting different worlds.

11 I am not going speculate on the reasons why the author is not using this freedom, but explanations, which take into account Tolkien’s obsession with the ‘historical truth’ of Middle-earth, which can only resemble ‘truth’ in reality if the history and makeup of Middle-earth also follow cause and effect-chains, seem to point in the right direction.

12 The questionability of the amount of determinism is only one point. Another point can be made by discussing the difference between foresight and determinism. Might it not be that Illuvatar has ‘only’ foreseen what would come? That he was omniscient but not almighty? That the happy ending of the Middle-earthian uni¬verse was due to most of its inhabitants being ‘good’ on a very basic level, so that evil could not persist? Other points could be made …

13 At least the Four Hobbits do not seem to have a very clear idea of the spiritual na¬ture of Middle-earth (see Weinreich 2005 for a discussion of their ethical motiva¬tions).

FRANK WEINREICH studied philosophy, communication sciences and politics in the early Nineties and holds a PhD in philosophy from the University of Vechta. He is working as independent scholar, freelance author and editor in Bochum, Germany since 2001. His interests focus on ethics, bioethics, media ethics, tech¬nology assessment, education, new media, fantasy and science fiction and, of course, on Tolkien’s works. He has published numerous books, articles and essays and is co-editor of Hither Shore, the Scholarly Journal of the German Tolkien Society and co-editor of Stein und Baum, a German source for fantasy literature and works on fantasy. He may most easily be contacted through his professional homepage www.textarbeiten.com or via his private Tolkien-Site which at the moment carries nearly forty articles, essays and stories on Tolkien and Middle-earth: www.polyoinos.de/tolk_stuff.

Bibliography

Beagle, Peter S., 1966, ‘Tolkien’s Magical Ring’, in J.R.R. Tolkien, The Tolkien Reader. Stories, Poems and Commentary by the Author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, New York: Ballantine Books, pp. IX-XVI.

Gleick, James, 1987, Chaos. Making a New Science, London, New York: Penguin.

Honegger, Thomas, Andrew James Johnston, Friedhelm Schneidewind, Frank Weinreich, 2005, Eine Grammatik der Ethik, Saarbrücken: Edition Stein und Baum.

Knoepfler, Nikolaus, 1997, ‘Das Leib-Seele-Problem und der Determinismus’, Philosophisches Jahrbuch 104, pp. 103-116.

Laplace, Pierre-Simon, 1995, Théorie analytique des probabilités, (reprint of the first edition, Paris 1847), Paris: Gabay.

Mayr, Ernst, 2000, Das ist Biologie. Die Wissenschaft des Lebens, Heidelberg, Berlin: Spektrum Verlag.

McKiernan, Dennis L., 2001, Once Upon a Winter’s Night, New York: RoC.

Sandkühler, Hans-Jörg (ed.), 1999, Enzyklopädie Philosophie, two volumes, Hamburg: Meiner.

Sandkühler, Hans-Jörg, 1999a, ‘Realismus’, in Hans-Jörg Sandkühler (ed.), Enzyklopädie Philosophie II, pp. 1346 – 1350.

Sandkühler, Hans-Jörg, 1999b, ‘Erkenntnistheorie/Erkenntnis’, in Hans-Jörg Sandkühler (ed.), Enzyklopädie Philosophie II, pp. 1039-1059.

Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel, 1988, Tree and Leaf, London: Grafton.

—, 1988a, ‘On Fairy Stories’, in J.R.R. Tolkien, Tree and Leaf, pp. 9-73.

Weinreich, Frank, 2005, ‘Ethos in Arda’, in Thomas Honegger et al., Eine Grammatik der Ethik, Saarbrücken: Edition Stein und Baum, pp. 111-134.

(Bochum 04/08)